Search your article

Pranayama Unveiled

Pranayama Unveiled

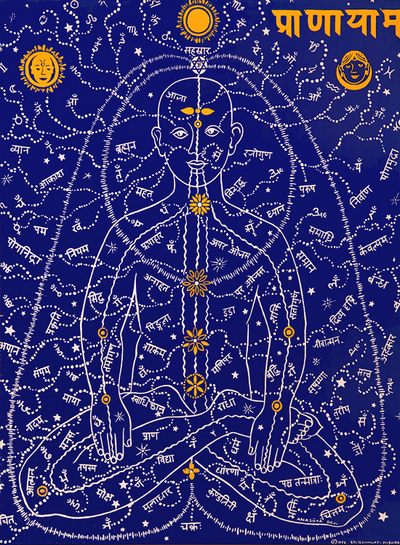

The techniques of pranayama are designed to bring the central Nadi, the Sushumna, into the primary function, rather than the Ida or Pingala dominating the functions of prana flow. With the activation of the Sushumna as the primary flow for prana, the yogi experiences freedom from the human condition, and joy. By opening up the flow of the Sushumna, the yogi raises kundalini, the sleeping serpent, from the root chakra, the Muladhara. This kundalini energy, which is very powerful, passes through and blows open each chakra. The resulting states of consciousness, represented by the thousand-petalled lotus, the crown chakra at the top of the head, is considered the highest state a person can reach in the human form. It is union with cosmic consciousness, beyond time and space, and also called shakti. The person merges his individual self, soul, or atman, with the cosmic soul, or Brahman. Pranayama is one of the pieces of raja yoga (royal yoga). The first four pieces are Yama (restraints), niyama (observances), asana (postures), and pranayama. The next four pieces of raja yoga are pratyahara (sense withdrawal), Dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (superconscious state, freedom from reincarnation cycles). Controlling breath and nerves results in controlling the mind, and controlling the mind results in freedom. According to yoga, the disease is the result of imbalance and blockage in the flow of prana. Psychologists have discovered that there is a connection between personality types and breathing patterns. The yogi believes that by changing the pattern of breathing, one can transform the personality. When the mind is disturbed, the breath is disturbed and vice versa. By making the breath deep, even, and smooth, the mind relaxes and thus the personality changes or the physical disease goes away [1].

Preparation

Patience and perseverance are necessary in spiritual life, and this is especially true for pranayama. The practitioner should not be frustrated if he cannot attain a certain ratio or number of rounds; it may take months or even years to perfect one pranayama alone. The regular practitioner is progressing all the time, although the progress cannot be seen objectively. So there is a tendency to think that nothing is happening; however, one should be assured that the practice is developing on both the gross and subtle levels.

In order to qualify for pranayama, it is highly recommended that one must first master yoga asanas. In order to reap the full benefit of asanas, one must undergo the process of Shatkarmas. The physical body is a combination and permutation of the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and ether. Shatkarmas purify these elements, so they do not interfere with the activities of prana. The effect of asanas and pranayamas increases substantially when the body is relieved of toxins. The body becomes sensitive and responds to the changes that an asana or pranayama demands from it.

The inner body of a pranayama practitioner needs to be pure. Adverse effects may be experienced if one practice Every practice should be treated with respect and caution. There should be no violent respirations, no extended Kumbhaka beyond a comfortable measure, no forcing of the breath, body, or mind. The practitioner should not attempt to perform advanced pranayama which is beyond his present capabilities. In this way, comfortable progress will be assured and one will be able to achieve full benefit from the wonderful science of pranayama. The Yoga Chudamani Upanishad states (v. 118): pranayama without removing the energy blocks and toxins accumulated on account of an irregular lifestyle. For example, the fermentation of mucus will immediately interfere with pranic activities. The practice of Shatkarmas gives a good flushing to the mouth, nose, stomach, intestines, and indeed the whole body. Neti kriya cleans the nasal passages and kunjal kriya removes mucus and hyperacidity from the stomach [1].

When Shatkarmas are followed by asanas, the pranas are able to penetrate each and every nerve, cell, and pore of the body. The practitioner will reap enormous benefits by following a routine of Shatkarmas, asanas, and pranayamas, even if he has completely neglected the body for years. However, if one has led a simple and balanced lifestyle, and maintained the purity of the body, then one can start directly with pranayama.

Diet

The practitioner of pranayama should choose a balanced diet that is suitable to his constitution. There is no one diet that is right or wrong for everyone. As the saying goes, “One man’s food is another man’s poison”. Food can be classified into three basic groups: (i) tamasic – which creates lethargy, dullness; (ii) rajasic – which creates excitement, passion and disease, and (iii) sattwic-which bestows balance, good health and longevity. Fresh and natural foods are sattwic; packaged and refined foods are tamasic and should be avoided. A diet of grains, pulses, fresh fruit and vegetables, and a small amount of dairy products is most beneficial. For nonvegetarians, a small portion of meat, fish or eggs may be added. The diet must also be adjusted to avoid constipation.

Place

Pranayama should be practiced in a clean environment to minimize the effects of pollution. One may practice in the open air or in a well-ventilated, clean, and pleasant room. One should never perform pranayama in a foulsmelling, smoky, or dusty room. Ideally, the place of practice should be somewhat isolated, away from people, noise, and interruptions. Avoid practicing in the sun or wind. The soft rays of the early morning sun are beneficial, but when they become stronger, they are harmful and the body will become overheated. Practicing in a draught or wind may cause chills and upset the body temperature.

Time of practice

Early morning is the best time to practice pranayama. At the time of Brahmamuhurta (between four and six am) the vibrations of the atmosphere are in their purest state. The body is fresh and the mind has very few impressions, compared to its state at the end of the day. Most pranayamas should not be done in the heat of the day (unless a special sadhana is given by the guru). The yogic texts advise four periods for the practice of pranayama: sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight, but this is for advanced practitioners only. Pranayama should not be practiced after meals. One must wait for three hours after a meal before practicing. An empty stomach ensures that the prana Vayus are not concentrated in the digestive process and can be used to initiate more subtle activities. At the same time, pranayama should not be practiced when one is very hungry [1].

Sequence

Pranayama should be performed after asanas and before meditation practices. After doing asanas, the practitioner may rest for five minutes and then begin pranayama. A few rounds of pranayama may also be practiced just before Japa and meditation. The mind becomes one-pointed and the body feels lighter after pranayama, and then meditation is more enjoyable.

Posture

The ability to sit comfortably in a meditation asana is a requisite for the successful practice of pranayama. The correct posture enables efficient breathing as well as the stability of the body during the practice. Both concentration and technique are hampered by poor posture. The chest, neck, and head must be in one vertical line during the practice so that the spinal cord remains straight. One should not allow the body to become crooked or to collapse. The body should not bend forwards or backwards or to the right or left. By regular practice, mastery over the pose will come by itself. The best postures for the practice of pranayama are padmasana, Siddhasana, Siddha yoni asana and Swastikasana. When one advances in the practice, prana moves through the body at a terrific speed. This movement must be supported by total immobility of the body, which these postures maintain. As the body produces more energy, it effectively turns into an electrical pole. The left side carries cool energy and the right warm energy, representing the negative and positive poles. The additional energy produced by the practice can escape through the earth connection. Therefore, a closed-circuit must be created to ensure that the energy remains within the body [1].

This circuit is made by the four meditation postures and strengthened by the application of mudras and bandhas. This may not apply to a beginner, but if one wants to advance in pranayama, then expertise in the meditation asanas is imperative. In the beginning, however, one may sit in Sukhasana (comfortable pose), especially if one is overweight.

Starting nostril

When alternate nostril breathing is used in Nadi Shodhana or bhastrika, usually the practice is begun from the left nostril. However, if the left nostril is blocked, one may begin with the right nostril. In the course of the practice, the blocked nostril will become free and open.

The nose

Respiration begins with the nose and the breath in the nostrils is closely related to many subtle balances in the body/mind system; therefore, attention should be paid to ensuring its efficient operation. The practice of pranayama is obstructed by chronic or acute nasal disabilities. All breathing should be through the nose except where otherwise specified. The nasal cavity should be regularly cleaned by Jala neti for the efficient operation of the nostrils. This will increase sensitivity to the action of the breath and prana. Nasal blockages caused by colds and allergies respond positively to this regular cleaning.

Flaring the nostrils

The practitioner should be aware of the nostrils throughout the practice of pranayama. Conscious breathing allows the air to enter the nostrils more easily, evenly and in greater volume. Control of the nostrils allows them to contribute to a greater receptivity of the entire respiratory system. Conscious control of the nostrils will develop with practice. Normally the nostrils barely move, if at all, during respiration. Ideally, however, the nostrils should expand outwards while inhaling and relax back to their natural position while exhaling. Flaring the nostrils is an important aspect of pranayama, particularly in bhramari, samavritti and nadi shodhana pranayamas. This simple practice alone will effectively facilitate the absorption of prana in the body, while increasing the air intake by up to ten percent.

Breathing

The breathing should become very subtle during the practice of pranayama. The gross breath can be felt at a distance of 2-36 finger-widths from the nose. The subtler breath extends for a shorter distance. The practitioner should breathe in such a way that the breath does not extend beyond two finger-widths during exhalation, and retention does not make one exhale forcefully. The internal retention should be adjusted, so that one does not gasp while breathing out. The speed of inhalation and exhalation should also be consistent and uniform. When one is tired, for example, the tendency is to inhale deeply and slowly and exhale quickly. When one is not tired, one may inhale more quickly and exhale slowly. This inconsistency in the breath creates uneven waves, which disturb the mind. There must also be uniformity in the breath. If a speedometer were placed inside the nose, one would see that the breath is never uniform. This is particularly noticeable after internal retention. During one exhalation, there may be up to ten different speeds. The breath should be smooth and uniform, without stops, jerks, or tremors.

Pranayama Practices